In our previous episode, we covered the evolution of the ancient Greek warfare

during the two Persian invasions, but we consciously avoided talking about the

Greek navies that played the essential role in this conflict. This video will

cover the naval warfare of the period.

Ancient Greek naval warfare was very closely related to land conflict, to the

point where it can be seen as a natural extension of the Greek land combat.

The navies were always close to the shore, to be quickly resupplied while the standard

ship formation in naval clashes looked much like a hoplite phalanx on a

bigger scale. Additionally, each city-state boasted its tactics and methods, as well as slight

variations in the type of vessels used, reflecting the highly-independent and

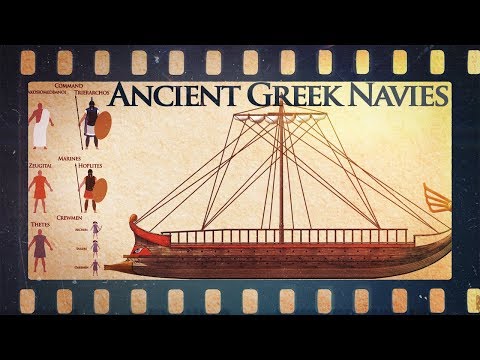

autonomous attitude of the ancient Greeks. At the time of the Greco-Persian Wars,

the Greeks used the trireme, which,

according to many scholars, was an adapted version of Phoenician ships

with two rows, called bireme. However, the trireme was a vessel ahead of its

time in many ways, and a masterpiece of Ancient Greek naval architecture,

which significantly contributed to the defense of Ancient Greece from foreign invasions,

but also to the expansion of Hellenic culture and ultimately the establishment

of the Mediterranean as the "Greek Sea." Thucydides stated that the Corinthians

were the first of the Greeks who adopted the particular ship around 700 BC.

Up until that moment, the Greek navies consisted mainly of the pentecounter, a vessel

with one row of 50 oarsmen, which can be regarded as its natural predecessor.

The trireme's average size was 37 meters, and its weight was 50 tons, which was big

enough to cause significant damage to enemy ships, but also light enough to be

transported by the crew on land, if necessary. Most importantly, it was made

out of pine and cypress wood, to be fast and agile. Its top speed was usually

around 8 to 10 knots, which allowed the commander to ram enemy vessels

with significant force. The ship was named after the three rows of oarsmen, who,

contrary to popular belief, were not slaves but often Greek citizens.

In fact, if slaves had to be used they would most likely be officially freed first.

Oarsmen were not tied to their seats and

were armed, to be able to board an enemy ship or defend their own.

Oarsmen in the top row were known as thranitai, while oarsmen in the second tier were

zygitai and finally the ones on the bottom of the ship were called thalamitai.

Xenophon mentions that thranitai were

respected by the rest of the crew because they were exposed to the weather

conditions and, most importantly, to enemy fire.

Naval warfare at the time looked much like a land battle on the sea since a

trireme would most regularly try to ram an enemy ship with its bronze ram – the emvolon

that was 2-3 meters long and was attached to the ship's keel and often

had the form of an animal. Ramming was followed by infantry boarding and clashes.

An average trireme had a 200 men crew: 7 officers, 170 oarsmen, 14

marines called epibatai - 10 hoplites and four archers - the toxotai as well

as nine sailors who were responsible for the ship's sails and general maintenance.

It has to be mentioned that these numbers vary according to the strategy

of each commander and the level of professionalism of the particular

city-state navy. For example, during the battle of Lade

in 494 BC the triremes from Chios each carried 40 hoplites as they relied on

the skills of their soldiers rather than the naval maneuvers of their captains.

Meanwhile, the Athenian navy, which was much more professional, preferred ramming

as the primary technique for defeating an enemy fleet and thus kept the numbers

of marines much lower, to be able to have more oars. Athenian triremes consistently

had approximately 14-15 marines, since maneuverability and speed, which were

valued naval skills for the democratic city-state, would otherwise be

jeopardized. For the Athenian navy, the hoplites were drawn from the Zeugitae

social class, while the archers, sailors, and oarsmen were recruited from the

lowest class of Thetes. Furthermore, the hoplites who mainly acted as a secondary weapon for

the ship after the ramming, were equipped perhaps with the standard hoplite

armor and arms along with the grappling hooks for boarding enemy ships, although

it is also likely that, especially Athenian marines were given slightly smaller shields and linothoraxes

instead of bronze armor.

. It seems, however, that the primary task of these forces was defensive, as they

were tasked with the protection of the oarsmen, arguably the most critical group

of the crew. The captain was called Trierarchos, almost always an Athenian noble

from the pentacosiomedimnoi class - the highest social class of the ancient Athens,

and was responsible for the ship's maintenance and operation, as well as

conscription and recruitment, not only from Athens but other Greek city-states too,

often Athenian allies. Also, the commander of the vessel was known as

Kybernetis and was usually an experienced seaman. The crew in

the Athenian navy was paid 1 Drachma for its services on a daily basis

while also receiving food rations. In general, funding the crews of

Athenian warships followed the democratic traditions of the city-state:

everyone was being paid the same amount; however, higher-ranked marines and officers

probably received some bonuses. Athenian naval power owed much to Themistocles.

He was the one who forced the state to build a fleet of 200 triremes in 483 BC

and also urged the people to leave Athens, after the Oracle of Delphi,

Pythia, advised the Athenians that "only the wooden walls will save you." A small group

of elders stayed behind and built a wooden wall close to the Acropolis,

but were quickly slaughtered by the advancing Persians, while the rest of the

population sailed away during. Despite the destruction of the city, the ships, acting as

wooden walls, saved not only Athens but the whole of Greece at the crucial

Battle of Salamis in 480 BC. The Athenian fleet was at large supported by the

wealthy citizens of Athens in what was known as liturgies, a practice where the

prosperous offered financial and physical aid for cultural,

military, social and economic purposes.

Finally, variations of the typical layout for the trireme emerged during the

Peloponnesian War mainly for the transportation purposes, with fewer

oarsmen and more hoplites or even horses, while artillery, such as ballistas

and catapults, became more widespread during the period. The naval tactics

developed to more complex movements with flanking the enemy fleet becoming a

well-established strategy or penetrating with force at a particular point so that

the enemy line would break. Naval warfare during the Peloponnesian War can be seen

as a reflection of the two leading city-states' traditions.

Sparta would rely more on the infantry's capabilities and would prefer to quickly ram Athenian

vessels head-on since it was almost impossible to compete with superior

Athenian maneuverability and their highly-skilled oarsmen, while Athens

would attempt to flank the enemy fleet while infantry and ranged troops

harassed the enemy. At last, the Peloponnesian War also saw an increase in fleet sizes with

as much as 300 ships and 60.000 seamen being involved in battles at

Arginusae and Aegospotami. The trireme's most significant disadvantage,

the incapability to be supplied with food and water for more than a day,

caused crashing defeat at the Battle of Syracuse, as well as the

aforementioned Battle of Aegospotami when the Athenian fleet was caught off-guard

while trying to procure food for its crews.

Thank you for watching our documentary covering the naval warfare of Ancient Greece

during the period of the Persian invasions. In our next video, we will

cover the Greek armies during the Peloponnesian Wars. We would like to

thank our Patreon supporters, who make the creation of these videos possible.

Also, Patreon is the best way to suggest a new video, learn about our schedule and

so much more. This is Kings and Generals channel,

and we will catch you on the next one.

For more infomation >> Law & Order: SVU - The End of Days (Episode Highlight) - Duration: 3:07.

For more infomation >> Law & Order: SVU - The End of Days (Episode Highlight) - Duration: 3:07.

For more infomation >> What We Owe to Those Who Loved Us in Childhood - Duration: 5:01.

For more infomation >> What We Owe to Those Who Loved Us in Childhood - Duration: 5:01.

For more infomation >> Scotts Miracle Gro closing in Pearl - Duration: 0:31.

For more infomation >> Scotts Miracle Gro closing in Pearl - Duration: 0:31.

For more infomation >> Former patients of raided pain clinics struggling to get help with medications - Duration: 3:31.

For more infomation >> Former patients of raided pain clinics struggling to get help with medications - Duration: 3:31.  For more infomation >> Video: Chance of showers, storms - Duration: 2:44.

For more infomation >> Video: Chance of showers, storms - Duration: 2:44.  For more infomation >> Stretch of Route 15 shut down - Duration: 0:45.

For more infomation >> Stretch of Route 15 shut down - Duration: 0:45.  For more infomation >> President Donald Trump Reimbursed Michael Cohen For Stormy Daniels Payment, Giuliani Says | TODAY - Duration: 4:09.

For more infomation >> President Donald Trump Reimbursed Michael Cohen For Stormy Daniels Payment, Giuliani Says | TODAY - Duration: 4:09.  For more infomation >> 2 Black Men Arrested At Philadelphia Starbucks Receive $1 Settlements | TODAY - Duration: 3:01.

For more infomation >> 2 Black Men Arrested At Philadelphia Starbucks Receive $1 Settlements | TODAY - Duration: 3:01.

For more infomation >> Bodycam Footage From Las Vegas Shooter's Suite Released | TODAY - Duration: 2:44.

For more infomation >> Bodycam Footage From Las Vegas Shooter's Suite Released | TODAY - Duration: 2:44.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét